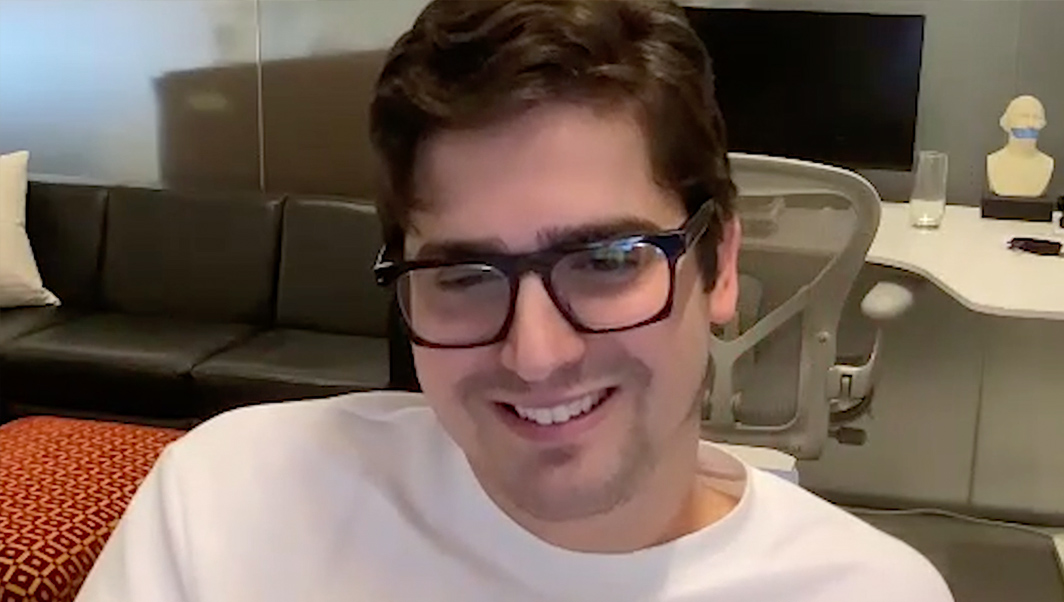

Exclusive Interview: Mark H. Rapaport Talks Feature Film Debut Hippo, Blurring Absurdity with Realism, Developing His Visual Language, and More

Mark H. Rapaport is a rising visionary in filmmaking, known for creating work that not only entertains and surprises but also invites audiences to probe deeper layers of meaning. His debut feature, Hippo, is a poignant, darkly humorous reflection on adolescence, rooted in his own tumultuous coming-of-age experiences.

“Though my mother would protest, Hippo is my attempt to capture the tumult of my teenage years,” Rapaport reveals. Raised in a deeply religious community where topics like sex were shrouded in silence and shame, his formative years were filled with guesswork, misunderstandings, and late-night internet searches.

Hippo serves as a comforting embrace to his younger self, like the parting words of a therapist you’re not quite ready to leave. Beyond that, the film is also a wry cautionary tale on the inescapable impact of family, as Rapaport puts it, “You can escape a monster, a ghost, even a vampire—but you cannot escape your DNA.”

Pop Culturalist was lucky enough to speak with Mark about Hippo, how he blurred absurdity with realism, developing his visual language, and more.

PC: You co-wrote this film with one of your best friends, Kimball [Farley], and the character of Hippo is a blend of your shared experiences. How did you find the intersection of your personal stories? How did those shape the nuances and depth of this character?

Mark: I generally consider myself—or at least, I try to be—a private person, but in my art, I can’t help myself. I bring together those two sides by creating a mask of absurdity based on my real life. I really did get that sex talk from my mom, telling me I’d wake up in a puddle of goo. I want to incorporate my personal experiences, but my life alone isn’t entertaining enough to just go with that. I’m not the kind of filmmaker who’s going to do a super deep drama that’s a straightforward coming-of-age story. So, I like to start with the personal as a jumping-off point and then take it somewhere insanely wild because I have fun with that. It feels more cathartic to live out the fantasies or crazy ideas of my teenage self rather than toning it down. Most people don’t kill a Craigslist predator—it’s not like that. But what I love about cinema is that you can do anything; you can invent the world. That’s what I tried to do—invent a world where we could both dive in and find comfort in revisiting our past.

PC: You’ve definitely accomplished that. There’s no film quite like this. Shooting in black and white was such a brilliant choice—it perfectly complements the coming-of-age themes you wanted to explore while also creating an intimate portrait of this nuclear family. How early in the process did you decide on this style, and how did that vision complement the story?

Mark: That’s a great question. The decision was twofold. First, a lot of first-time filmmakers go for black and white—like Christopher Nolan’s Following and Darren Aronofsky’s Pi. Many filmmakers end up making that choice, often because of budget constraints. It was something I was considering if we faced budget challenges, as a way to keep it simple. At the same time, I was rediscovering my love for black-and-white photography, inspired by classic [Ingmar] Bergman films, Orson Welles, and more recent films like Cold War and Ida. I realized that there’s something haunting and surreal about black and white that felt perfect for this story.

I discussed it with William Babcock, our cinematographer, and we agreed that black and white would soften the absurdity of the script and these characters, who might otherwise come off as too wacky. We didn’t want to make a “wacky” movie; we wanted something real that hits you but is also a bit insane. Black and white really helped achieve that. I can’t imagine the movie in any other way—I want to shoot in black and white again.

PC: Tonally, there’s such an interesting contrast where the situation feels very real for these characters, yet audiences find humor in the absurdity. How did you manage to strike that balance so seamlessly, playing in an almost fantasy realm while keeping it grounded in reality? As the director and co-writer, how do you create that space for your ensemble to explore those dynamics?

Mark: That’s another great question. The cast are dramatists first, not comedians. Although I started my career in comedy, standup, and improv before moving into film, I consider myself a serious person at heart. I like to use comedy not as the goal of any scene, but as a way to gain insight into characters. For me, there’s always a reason behind it. By focusing on story and performance first, comedy becomes an added bonus when everything else is clicking. When the actors fully commit to their characters, like Buttercup genuinely believing her brother is mentally ill or Kimball embodying that intensity—even doodling obsessively in character—it creates an environment where the absurdity emerges naturally without it feeling like an SNL sketch. I never wanted to create an SNL character, but I did want it to be just as funny. Shows like The Office achieve that because everyone fully buys into their characters, and I love when characters can play both sides.

I think of this film as a “tragic comedy,” and that’s what I hope it achieves. I didn’t want a sad ending; I always want to instill some hope in my films. That tone is captured in the last scene, where there’s something both funny and poignant about being in a bomb shelter with your baby—it’s beautifully simple. I tried to capture both sides as best as possible.

PC: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that Eric and Eliza Roberts embody the spirit of indie filmmaking. How did the trust they placed in you inspire you to take more creative risks?

Mark: Eliza is like an L.A. mother to me and another L.A. mother to Kimball. They’re such incredibly generous people who just want to work, make art, and act. They’re not pretentious. There’s a reason Eric has 600 credits—he genuinely loves what he does. As they say, if you love what you do, it never feels like work, and that’s something I strive for.

When I first met Eric and Eliza on Andronicus, I was definitely a bit intimidated. I didn’t know what to expect—I was thinking, “Do we have them in a five-star hotel? Do they have their taxi? Are all their needs met?” But then Eliza arrives on set, totally relaxed, saying, “Everything’s fine. Don’t worry, we’ll figure it out.” It’s amazing to have that kind of mentor on a project. We’re all young—I’m young, and so are Kimball and Lilla [Kizlinger]—and then we have these mentors in Eric and Eliza. Eliza was more involved on this one since Eric did voiceover, but it’s so valuable to have that support from an accomplished actor. I think every filmmaker should cast an older legendary actor—it really pays off.

PC: This is also your feature debut. Congratulations, by the way—what a statement you’ve made with this project. What did you learn from this experience—aside from wanting to shoot in black and white again—that you’ll bring to your next project? And what is that next project?

Mark: For me, I’m really proud of the script I wrote for Hippo. One thing I always want to remember is to put the script on a pedestal and make it the best it can be. Never underestimate the importance of the writing process. I want to continue building on that and keep getting better at it. My goal is to keep making stories that surprise people, make them feel something, and entertain them.

I wasn’t the friend holding the camera growing up; I had a friend who did that. I came into this more as a writer. Working with our cinematographer, Will Babcock, taught me a lot about visual storytelling. I’m always developing my visual language—I know my writing can get better, but I still see myself as a stronger writer than cinematographer, which is why I collaborate with talented people like Will. What he achieved on a low budget is better than what most studio movies do with 30 times the budget. I remind myself that movies aren’t just about storytelling; they’re also about creating a visual experience. It’s not a podcast or a book. If we’re not challenging the audience or myself visually, then we’re not doing the full job. Hippo pushed me visually, and I want to keep pushing those boundaries in every project.

Next up is another black-and-white film called Godhead, which I’m hoping to shoot in January with Kimball, Sarah Coffey, and Al Warren, who also worked on Dogleg. Will Babcock will be the cinematographer again, and we’re aiming to take this black-and-white style into a more Hitchcockian thriller. We’ll be shooting it on a low budget, in a single location, but we want to make it as crazy and wild as possible.

To keep up with Mark, follow him on X and Instagram. Hippo is in select theaters now.

Recent Posts

With ‘Warfare,’ Ray Mendoza and Alex Garland Deliver the Most Unflinching War Film in Years

Warfare opens with no introductions, no origin stories, no guiding hand. What follows is not…

Exclusive Interview: Christopher Landon on Blending Suspense, Heart, and Nostalgia in ‘Drop’

Christopher Landon has long been a master of genre reinvention. From the biting satire of…

Win Tickets to a NYC Screening of Sinners

Pop Culturalist is excited to be partnering with Warner Bros. Pictures to give away tickets…

“She’s Hugh’s First Victim”: Danielle Savre Breaks Down Lena’s Past, Present, and What Could Be Ahead on ‘Found’

Ever since Danielle Savre joined Season 2 of Found as Heather, fans have been trying…

Exclusive Interview: Marc Underhill Is Making Space for the “B” in LGBTQ+ with ‘Practically Gay’—One Honest Story at a Time

Media has the power to reflect the world as it is. But for many bisexual…

Win Tickets to a NYC Screening of G20

Pop Culturalist is excited to be partnering with Prime Video to give away tickets to…